Narratives Strategies for Racial Justice: The Visuality of Truth Telling

This past weekend, I joined 60 fellow NYU graduate students on a powerful and deeply moving journey to Montgomery, Alabama, where we visited The Legacy Sites. As part of our course, Narrative Strategies for Racial Justice and Equality, led by Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative, we spent time at the EJI offices, walked through the Legacy Museum, reflected at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and previewed the soon-to-open Freedom Monument Sculpture Park. This blog post draws from my reflection notes during my visit to The Memorial for Peace and Justice and is part of a larger academic paper I submitted for this course. My final paper explores the various visual methods used at The Legacy Sites to articulate decolonial aesthetic representations and narratives, which are essential to achieving justice and healing.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice stands as a solemn, necessary space to confront the enduring legacy of racial terror in America. As the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the Black lives lost to lynching, it honors more than 4,000 victims of racial violence - names etched into steel, suspended in silence. It urges visitors not only to remember, but to reckon. You can learn more about the Memorial and the vital work of truth-telling it represents here.

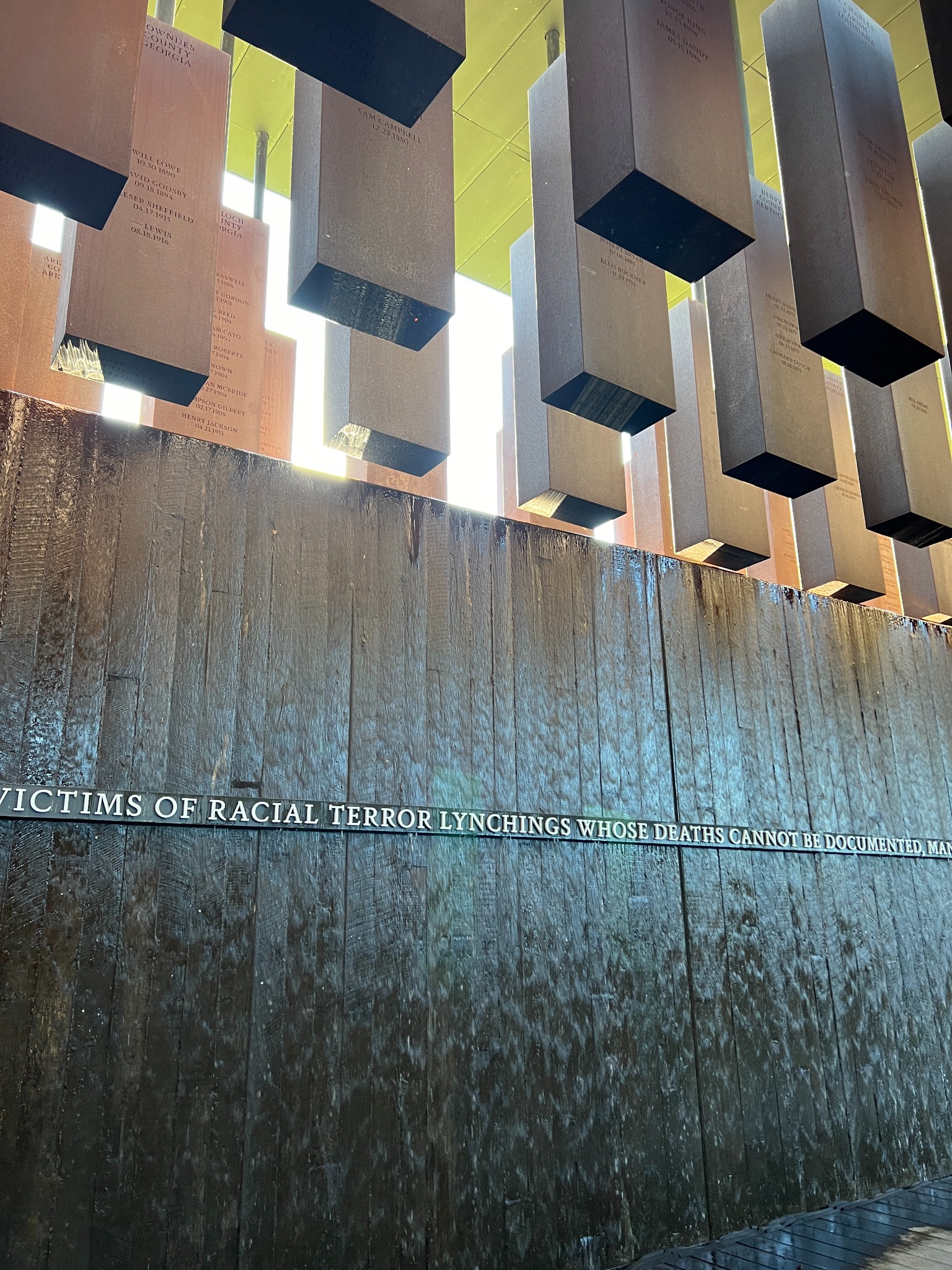

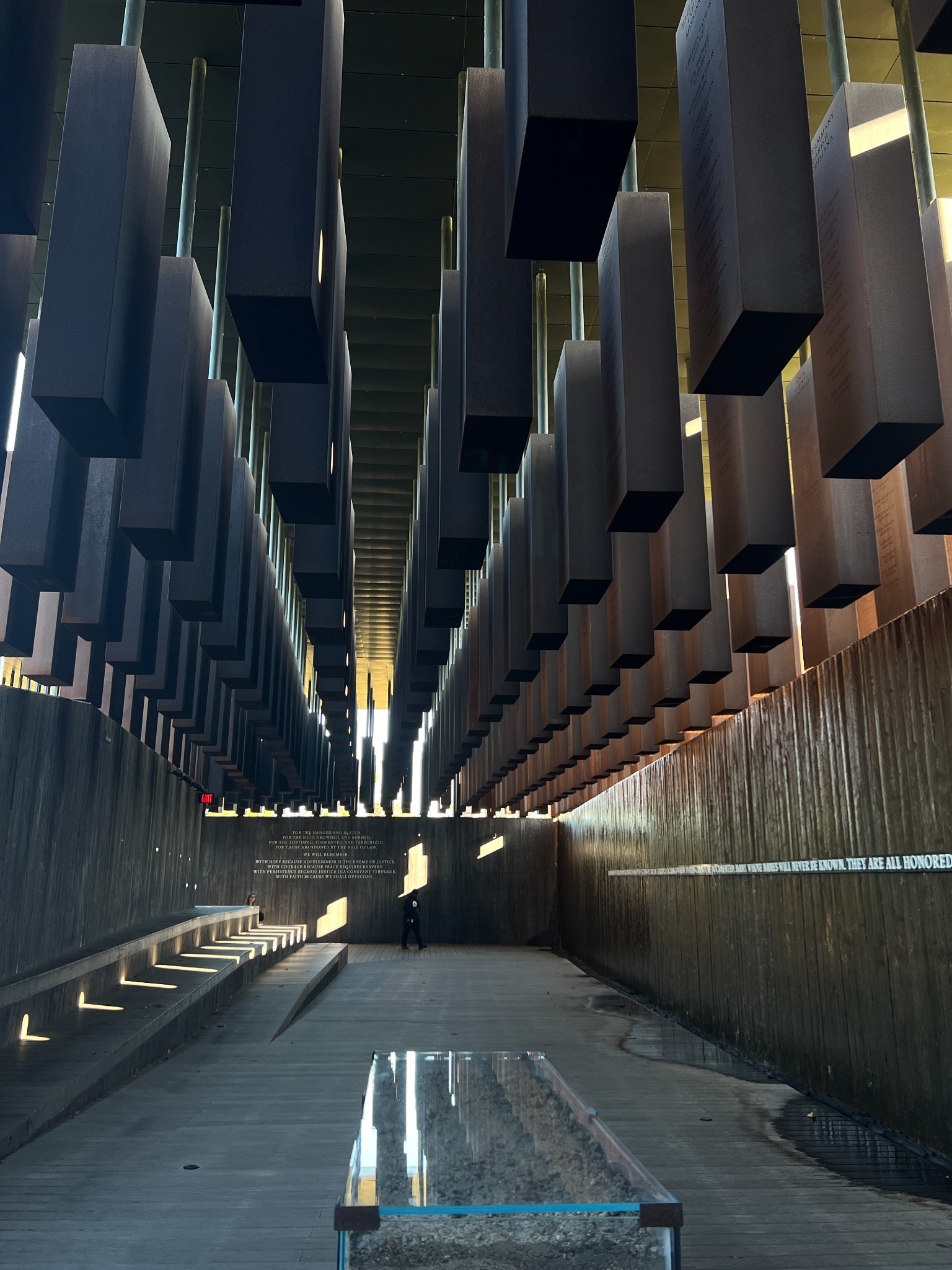

When I first entered the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, I was met with 800 towering, copper-colored steel monuments. At the entrance, they rested on the ground -solid, grounded, almost inviting. But as I moved through the space, the pathway began to slope. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the monuments began to rise.

At first, they met my gaze at eye level. Then they lifted further, suspended high above me, until I found myself walking beneath them. I looked up, at the names, counties, and dates etched into the steel, each one marking a life taken by racial terror. The physicality of the space made the history inescapable. I wasn’t just observing it. I was inside it.

At one point, I was close enough to reach out and touch a monument. But I didn’t. Instead, I stood there, looking up, feeling the gravity of what I was witnessing. The design seemed to demand it: Look at this history. Look at what happened.

Near the end of the memorial’s path, I came upon a wall where water streamed down in silence. I asked a staff member about it, and he explained: the water represents tears. A tribute to the pain endured, the lives lost, and the grief left behind. It was a moment of mourning, but also of remembrance and reverence.

Descending into the next section of the memorial, I saw the same steel monuments again, only this time they lay flat across the ground like tombstones. The shift in position changes everything. The hanging structures confront you with the scale and violence of the loss. They force you to face a truth that has been hidden. The horizontal ones invite something else. They invite mourning. They feel closer, more personal. We don’t just witness the pain, we sit with it. We identify with the loss.

Seeing the same names repeated brought up a feeling of disbelief. How did this happen over and over again, and yet no one was ever held accountable? The repetition is haunting. It reminds us that these were not isolated acts of violence but part of a sustained campaign to terrorize and dehumanize.

The design of these monuments, whether suspended or grounded, confronts a version of history that many were taught to ignore. I kept thinking about something I heard in the museum, and again from our shuttle driver on the way to the site: “These are all cold cases.” That sentence stayed with me. The trauma of these spectacle lynchings didn’t just end with the act itself. It lived on in the communities, in the families, in every Black person who had to navigate life under that constant threat.

The breeze is fresh. It’s quiet. Birds chirp in a melody that feels rare and deliberate. There is peace here, a peace that feels honest. Unlike the museum, this space doesn’t present an abundance of information. It offers something else. It offers the truth.

By the time I arrive at the Memorial, hours after walking through The Legacy Museum, I am, as Nicholas Mirzoeff might say, fully de-anesthetized. I pause beside the flat monuments, letting the weight of the moment settle in.

My name is Manahil Munim. It’s not a common name, especially not in North America. I rarely encounter it in public spaces. Still, I try to imagine what it would be like to walk through this memorial and see my last name. My first name. A family name. I sit with that thought, and for a moment, I can’t move.

There are visitors who come here and find names that belong to their bloodlines. Their communities. Their histories. That’s what makes this space so powerful. That’s what activates the visible.

This is not just a memorial to the past. It is a mirror for the present. We are still living within this history. We are still shaped by it. I think about the people who once gathered to watch and cheer at lynchings, who saw terror and called it justice. Many of their descendants walk freely, untouched by the violence that shaped this country. Unbothered by the truth this space demands us to face.

And this is why narrative work matters. Because what we choose to remember, and what we choose to forget, continues to shape who we are.

As I approach the third area of monuments, I read a sign that reads “Community Reckoning”, a section honoring communities that have engaged in local remembrance and reckoning with the history of lynching and racial terror. I sit down in front of a plaque and begin to read the memorial text describing the lynchings.

A pattern emerges across the stories. Again and again, the message is clear: when the racial power hierarchy was challenged, even slightly, the response was brutal, swift, and public. The goal was to kill the Black person and instill enough fear that their family, and often their entire community, would flee. The violence was a tactic of control.

What haunts me most are the stories without names. The entries where the victims are only described by time, place, or accusation. No name, no family, no record of who they were. I’m brought back to a moment earlier at The Legacy Museum, where I read post-emancipation newspaper clippings - ads placed by newly freed Black people desperately searching for loved ones lost during slavery. The pain of separation, of being ripped from those who knew and loved you, echoes here too.

These unnamed victims were stripped of identity and memory. Dehumanized to the point that not even their names were preserved. The violence was not only physical, it was erasure. As Bryan Stevenson writes, Black people were not seen as human, and so white people became desensitized to the horror of what they were doing.

Still, I struggle to understand how anyone could commit such acts with their own hands, in full view of others, and convince themselves, and their communities, that it was right. That it was justice.

This visit didn’t just teach me about the past, it changed me. It reaffirmed that narrative work, rooted in truth and remembrance, is not only essential to justice, but to healing the future we all share.

Post a comment